Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Goddess of Sirius

Green Dragon Synchronicity

In Egyptian mythology, Sopdet was the deification of Sothis, a star considered by almost all Egyptologists to be Sirius. The name Sopdet means (she who is) sharp in Egyptian,

a reference to the brightness of Sirius, which is the brightest star in

the night sky. In art she is depicted as a woman with a five-pointed

star upon her head.[1]

Just after Sirius has a heliacal rising in the July sky, the Nile River begins its annual flood, and so the ancient Egyptians connected the two. Consequently Sopdet was identified as a goddess of the fertility of the soil, which was brought to it by the Nile's flooding. This significance led the Egyptians to base their calendar on the heliacal rising of Sirius.[1]

Sopdet is the consort of Sah, the constellation of Orion, near which Sirius appears, and the god Sopdu was said to be their child. These relationships parallel those of the god Osiris and his family, and Sah was linked with Osiris, Sopdet with Isis, and Sopdu with Horus.[1] She is said in the Pyramid Texts to be the daughter of Osiris.

Isis

Hathor

By the ancient Egyptians, Sirius was revered as the Nile Star, or Star of Isis. Its annual appearance just before dawn at the June 21 solstice, heralded the coming rise of the Nile, upon which Egyptian agriculture depended. This particular helical rising is referred to in many temple inscriptions, wherein the star is known as the Divine Sepat, identified as the soul of Isis.

For example, in the temple of Isis-Hathor at Dedendrah, Egypt, appears the inscription, "Her majesty Isis shines into the temple on New Year's Day, and she mingles her light with that of her father on the horizon." The Arabic word Al Shi'ra resembles the Greek, Roman, and Egyptian names suggesting a common origin in Sanskrit, in which the name Surya, the Sun God, simply means the "shining one."

For up to 35 days before and 35 days after our sun conjuncts the star Sirius ~ close to July 4 ~ it is hidden by the sun’s glare. The ancient Egyptians refused to bury their dead during the 70 days Sirius was hidden from view because it was believed Sirius was the doorway to the afterlife, and the doorway was thought to be closed during this yearly period.

In mythology

the dog Sirius is one of the watchmen of the Heavens, fixed in one

place at the bridge of the Milky Way, keeping guard over the abyss

into incarnation. Its namesake the Dog Star is a symbol of power, will

and steadfastness of purpose, exemplifying the initiate who has succeeded

in bridging the lower and higher consciousness.

In mythology

the dog Sirius is one of the watchmen of the Heavens, fixed in one

place at the bridge of the Milky Way, keeping guard over the abyss

into incarnation. Its namesake the Dog Star is a symbol of power, will

and steadfastness of purpose, exemplifying the initiate who has succeeded

in bridging the lower and higher consciousness.

Located just below the Dog Star is the constellation called Argo, the Ship. Astrologically this region in the sky has been known as the River of Stars, gateway to the ocean of higher consciousness.

The Chinese recognized this area as the bridge between heaven and hell ~ the bridge of the gatherer, the judge. In the higher mind are gathered the results of the experiences of the personality.

Between each life the Soul judges its past progress, and also the conditions needed to aid its future growth. As long as it is attached to desire, sensation, and needs experiences, the Soul continues to come into incarnation. Until it is perfected, the Soul cannot pass over, or through, the Bridge.

The association of Sirius as a celestial dog has been consistent throughout the classical world; even in remote China, the star was identified as a heavenly wolf. In ancient Chaldea (present day Iraq) the star was known as the "Dog Star that Leads," or it was called the "Star of the Dog." In Assyria, it was said to be the "Dog of the Sun." In still older Akkadia, it was named the "Dog Star of the Sun."

In Greek times Aratus referred to Canis Major as the guard dog of Orion, following on the heels of its master and standing on its hind legs with alpha star Sirius carried in its jaws. The concept of the mind slaying the real can be seen in the tales which relate the dog as the hunter and killer ~ the hound from hell.

Manilius called Canis Major the "dog with the blazing face." Also called the Large Dog, Sirius appears to cross the sky in pursuit of the Hare, represented by the constellation Lepus under Orion's feet.

Mythologists such as Eratosthenes said that the constellation represents Laelaps, a dog so swift that no prey could escape it. Laelaps had a long list of owners. One story says it is the dog given by Zeus to Europa, whose son Minos, King of Crete, passed it on to Procris, daughter of Cephalus. The dog was presented to Procris along with a javelin that could never miss. Ironically, Cephalus accidentally killed her while out hunting with Laelaps.

Cephalus inherited the dog and took it with him to Thebes, north of Athens, where a vicious fox was ravaging the countryside. The fox was so swift that it was destined never to be caught ~ yet Laelaps the hound was destined to catch whatever it pursued.

Off they went, almost faster than the eye could follow, the inescapable dog in pursuit of the uncatchable fox. At one moment the dog would seem to have its prey within grasp, but could only close its jaws on thin air as the fox raced ahead of it again. There could be no resolution of such a paradox, so Zeus turned them both to stone and placed the dog in the sky without the fox.

In the Chinese tradition, there is a remarkable analogy in the double meaning of the word Spirit and the word Sing (star). Shin and Sing, the Chinese words for soul and essence, are often interchangeable, as they are in the English language.

It is said that the fixed stars, and their domain, contain the essences or souls of matter ... a living soul is a higher essence of matter, and when evolved may also be called a star. These stars and essences become gods.

Like souls, stars are regarded as having divine attributes. Stars look down from regions of chaotic, violent, purity onto the world of humanity and influence the energies of humankind invisibly, yet most powerfully.

http://www.mirrorofisis.freeyellow.com/id63.html

http://www.siriusascension.com/sirius.htm

by Robert K. G. Temple

1976

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Sopdet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goddess of star Sirius | ||||

Sopdet in red dress, with star on the head

|

||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

|

|||

| Symbol | star | |||

| Consort | Sah (constellation of Orion) | |||

| Parents | Ra | |||

| Offspring | Sopdu | |||

Just after Sirius has a heliacal rising in the July sky, the Nile River begins its annual flood, and so the ancient Egyptians connected the two. Consequently Sopdet was identified as a goddess of the fertility of the soil, which was brought to it by the Nile's flooding. This significance led the Egyptians to base their calendar on the heliacal rising of Sirius.[1]

Sopdet is the consort of Sah, the constellation of Orion, near which Sirius appears, and the god Sopdu was said to be their child. These relationships parallel those of the god Osiris and his family, and Sah was linked with Osiris, Sopdet with Isis, and Sopdu with Horus.[1] She is said in the Pyramid Texts to be the daughter of Osiris.

Isis

Hathor

Sirius, aka Alpha Canis Majoris, aka Number

One Big Dog Star, is the brightest star in the sky, blazing away at an

apparent magnitude of -1.43. (The

latter is meaningless to most folks... except to note that Sirius is so

bright relative to the other stars that it’s off the astronomer’s

magnitude scale. Siriusly.) Sirius has a long history of observation (and speculation). Its

connection to ancient Egypt is perhaps the most notorious, but other

cultures were heavily invested in an apparent appreciation of the star

as well.

Astronomers at Louisville, Kentucky, noted

the Dog Star’s veneration in ancient Mesopotamia, where its “old

Akkadian name was Mul-lik-ud” (“Dog Star of the Sun”) and in Babylonia,

Kakkab-lik-ku (“Star of the Dog”). Assyrians, not to be outdone, called

Sirius, Kal-bu-sa mas (“the Dog of the Sun”), and in Chaldea, the star

was Kak-shisha (“the Dog Star that Leads”) or Du-shisha (“the

Director”). The later Persians referred to Sirius as Tir, meaning “the

Arrow.”

Sirius has been identified by some as the

Biblical star Mazzaroth (the Book of Job, 38:32). The Semitic name for

Sirius was Hasil, while the Hebrews also used the name Sihor -- the

latter an Egyptian name, learned by the Hebrews prior to their Exodus.

Phoenicians called Sirius, Hannabeah (“the Barker”.), a name also used

in Canaan. Meanwhile, The Dogon Tribe,

from the Homburi Mountains near Timbuktu (West Central Sahara Desert in

Africa), have an apparent lock on traditions as they were able to

describe in detail the three stars of the Sirian system.

But ancient Egypt provides the most regal history for Sirius. Initially, it was Hathor, the great mother goddess, who was identified with Sirius. But Isis soon became the major archetype, sharing honors with the title of Sirius as the Nile Star. An icon of Sirius as a five-pointed star (shades of the Golden Mean) has been found on the walls of the famous Temple of Isis/Hathor at Denderah. [The latter is possibly well connected to the Starfire of Laurence Gardner’s research. See, in particular, Gardner’s book, Lost Secrets of the Sacred Ark, HarperCollins, London, 2003; for some good stuff on Hathor and Denderah.]

But Isis was not a lone goddess. Instead, her husband was Osiris (Orion), and the Sirius star system is thought by

some to be Isis (Sirius A), Osiris (Sirius B), and the Dark Goddess as

Sirius C (which apparently exists, but has not be seen directly by

anyone other than the mentor of the Dogons).

[It is worth noting that Sirius B is a white

dwarf star (one with the mass of our sun, packed into a sphere roughly

four times that of the earth -- and thus with a density 3000 times that

of diamonds, a hardness 300 times that of diamonds, and by virtue of its

spinning on its axis every 23 minutes, the possessor of a huge magnetic

field). Sirius B, then being the archetype of a collapsed star, appropriately describes the death and diminution of Osiris. The Dogon Tribe obviously had connections with those in the know!]

It might also be noted that instead of the

Dark Goddess, the third alleged member of the Sirian system may also be

represented by Anubis, the dog or jackel-headed son/god of Isis and

Osiris, who assisted in the passage of the souls into the underworld. Anubis was the one who weighed the hearts of the dead to determine if their good deeds outweighed their not-so-good acts. Thus

both Anubis and the Dark Goddess were feared by the evil doers, most

Republicans and Democrats, and a fair number of Independents.

Sirius is also ancient Egypt’s inspiration for one of its first Calendars, a solar one with 12 thirty day months. In

the Egyptian Sirius calendar, the year began with the helical rising of

Sirius on or near the Summer Solstice (the first day of summer, the

longest day of the year, and the day when the noon sun stood highest

above the horizon). This “helical rising” is named after the Greek word

Helios for Sun.

The fact that the early Egyptian calendar

only had 360 days might be of concern to anyone who notes that in a mere

ten years, the calendar (and the harvest, flooding of the Nile, etc)

would be roughly 53 days out of sync. Accordingly, at some point, five feast days were added to the end of the year. Interestingly, however, this is considerable evidence to suggest that at the time, the Earth did in fact rotate in 360 days. Then, according to Immanuel Velikovsky, a close encounter by the Earth with Venus resulted in a change in the number of days in the year from 360 to 365.24. At that point of Ages in Chaos, the five feast days were added.

The feast days, by the way, “celebrated” the births of five gods (and goddesses):

Day One: Osiris,

Day Two: Horus (Heru-ur or Aroueris),

Day Three: Set,

Day Four: Isis, and

Day Five: Nephthys.

According to E. A. Wallis Budge, [Egyptian Magic, London, 1901]. The first, third and fifth feast days were considered unlucky. This

might have been due to the fact that Osiris was best known as the slain

god, while Set and Nephthys were the dark god, dark goddess

respectively. The second and fourth days, however, were lucky, with both Horus and Isis being winged/ascended. Apparently, being dead or dark was not much of a celebration.

Wish upon a star...

The Sirius Mystery excerpt-

Sirius,

The God * Dog Star

The effect of Sirian energy and influences generated approximately 18 years ago, in 1993 / 1994 (the last cycle when Sirius A and B were closest), have created renewed interest in this most influential heavenly body. The history books and religions of the world have had much to say about the God * Dog star. This article reflects on our ancestors' beliefs and inspired insights into a great mystery ~ the mystery of the Dog Star and its influences on our little corner of the universe.Sirius was an object of wonder and veneration to all ancient peoples throughout human history. In the ancient Vedas this star was known as the Chieftain's star; in other Hindu writings, it is referred to as Sukra, the Rain God, or Rain Star. The Dog Star is also described as "he who awakens the gods of the air, and summons them to their office of bringing the rain."

By the ancient Egyptians, Sirius was revered as the Nile Star, or Star of Isis. Its annual appearance just before dawn at the June 21 solstice, heralded the coming rise of the Nile, upon which Egyptian agriculture depended. This particular helical rising is referred to in many temple inscriptions, wherein the star is known as the Divine Sepat, identified as the soul of Isis.

For example, in the temple of Isis-Hathor at Dedendrah, Egypt, appears the inscription, "Her majesty Isis shines into the temple on New Year's Day, and she mingles her light with that of her father on the horizon." The Arabic word Al Shi'ra resembles the Greek, Roman, and Egyptian names suggesting a common origin in Sanskrit, in which the name Surya, the Sun God, simply means the "shining one."

For up to 35 days before and 35 days after our sun conjuncts the star Sirius ~ close to July 4 ~ it is hidden by the sun’s glare. The ancient Egyptians refused to bury their dead during the 70 days Sirius was hidden from view because it was believed Sirius was the doorway to the afterlife, and the doorway was thought to be closed during this yearly period.

Located just below the Dog Star is the constellation called Argo, the Ship. Astrologically this region in the sky has been known as the River of Stars, gateway to the ocean of higher consciousness.

The Chinese recognized this area as the bridge between heaven and hell ~ the bridge of the gatherer, the judge. In the higher mind are gathered the results of the experiences of the personality.

Between each life the Soul judges its past progress, and also the conditions needed to aid its future growth. As long as it is attached to desire, sensation, and needs experiences, the Soul continues to come into incarnation. Until it is perfected, the Soul cannot pass over, or through, the Bridge.

The association of Sirius as a celestial dog has been consistent throughout the classical world; even in remote China, the star was identified as a heavenly wolf. In ancient Chaldea (present day Iraq) the star was known as the "Dog Star that Leads," or it was called the "Star of the Dog." In Assyria, it was said to be the "Dog of the Sun." In still older Akkadia, it was named the "Dog Star of the Sun."

In Greek times Aratus referred to Canis Major as the guard dog of Orion, following on the heels of its master and standing on its hind legs with alpha star Sirius carried in its jaws. The concept of the mind slaying the real can be seen in the tales which relate the dog as the hunter and killer ~ the hound from hell.

Manilius called Canis Major the "dog with the blazing face." Also called the Large Dog, Sirius appears to cross the sky in pursuit of the Hare, represented by the constellation Lepus under Orion's feet.

Mythologists such as Eratosthenes said that the constellation represents Laelaps, a dog so swift that no prey could escape it. Laelaps had a long list of owners. One story says it is the dog given by Zeus to Europa, whose son Minos, King of Crete, passed it on to Procris, daughter of Cephalus. The dog was presented to Procris along with a javelin that could never miss. Ironically, Cephalus accidentally killed her while out hunting with Laelaps.

Cephalus inherited the dog and took it with him to Thebes, north of Athens, where a vicious fox was ravaging the countryside. The fox was so swift that it was destined never to be caught ~ yet Laelaps the hound was destined to catch whatever it pursued.

Off they went, almost faster than the eye could follow, the inescapable dog in pursuit of the uncatchable fox. At one moment the dog would seem to have its prey within grasp, but could only close its jaws on thin air as the fox raced ahead of it again. There could be no resolution of such a paradox, so Zeus turned them both to stone and placed the dog in the sky without the fox.

In the Chinese tradition, there is a remarkable analogy in the double meaning of the word Spirit and the word Sing (star). Shin and Sing, the Chinese words for soul and essence, are often interchangeable, as they are in the English language.

It is said that the fixed stars, and their domain, contain the essences or souls of matter ... a living soul is a higher essence of matter, and when evolved may also be called a star. These stars and essences become gods.

Like souls, stars are regarded as having divine attributes. Stars look down from regions of chaotic, violent, purity onto the world of humanity and influence the energies of humankind invisibly, yet most powerfully.

In June of 1993, as our sun covered Sirius from the Earth's view, the largest flood of the past century occurred. The waters of the Mississippi, the Nile River of the U.S., overflowed its banks. The flood that year continued until the middle of August. When Sirius re-appeared from behind the sun, the flood waters receded and the immediate life-threatening crisis subsided. Could this have been a reflection of the great rivers of energies streaming out from Sirius?

http://www.souledout.org/cosmology/sirius/siriusgodstar.html

http://www.mirrorofisis.freeyellow.com/id63.html

http://www.siriusascension.com/sirius.htm

by Robert K. G. Temple

1976

Sirius was the most important star in the sky to the ancient Egyptians. The

ancient Egyptian calendar was based on the rising of Sirius. It is

established for certain that Sirius was sometimes identified by the ancient

Egyptians with their chief goddess Isis.

The companion of Isis was Osiris, the chief Egyptian god. The 'companion' of the constellation of the Great Dog (which includes Sirius) was the constellation of Orion. Since Isis is equated with Sirius, the companion of Isis must be equated, equally, with the companion of Sirius. Osiris is thus equated on occasion with the constellation Orion.

We know that the 'companion of Sirius' is in reality Sirius B. It is conceivable that Osiris-as-Orion, 'the companion of Sirius,' is a stand-in for the invisible true companion Sirius B.

'The oldest and simplest form of the name' of Osiris, we are told, is a hieroglyph of a throne and an eye. The 'eye' aspect of Osiris is thus fundamental. The Bozo tribe of Mali, related to the Dogon, call Sirius B 'the eye star'. Since Osiris is represented by an eye and is sometimes considered 'the companion of Sirius', this is equivalent to saying that Osiris is 'the eye star', provided only that one grants the premise that the existence of Sirius B really was known to the ancient Egyptians and that 'the companion of Sirius' therefore could ultimately refer to it.

The meanings of the Egyptian hieroglyphs and names for Isis and Osiris were unknown to the earliest dynastic Egyptians themselves, and the names and signs appear to have a pre-dynastic origin -- which means around or before 3200 B.C., in other words 5,000 years ago at least. There has been no living traditional explanation for the meanings of the names and signs for Isis and Osiris since at least 2800 B.C. at the very latest.

'The Dog Star' is a common designation of Sirius throughout known history. The ancient god Anubis was a 'dog god', that is, he had a man's body and a dog's head.

In discussing Egyptian beliefs, Plutarch says that Anubis was really the son of Nephthys, sister to Isis, although he was said to be the son of Isis. Nephthys was 'invisible', Isis was 'visible'. (In other words, the visible mother was the stand-in for the invisible mother, who was the true mother, for the simple reason that the invisible mother could not be perceived.)

Plutarch said that Anubis was a

The companion of Isis was Osiris, the chief Egyptian god. The 'companion' of the constellation of the Great Dog (which includes Sirius) was the constellation of Orion. Since Isis is equated with Sirius, the companion of Isis must be equated, equally, with the companion of Sirius. Osiris is thus equated on occasion with the constellation Orion.

We know that the 'companion of Sirius' is in reality Sirius B. It is conceivable that Osiris-as-Orion, 'the companion of Sirius,' is a stand-in for the invisible true companion Sirius B.

'The oldest and simplest form of the name' of Osiris, we are told, is a hieroglyph of a throne and an eye. The 'eye' aspect of Osiris is thus fundamental. The Bozo tribe of Mali, related to the Dogon, call Sirius B 'the eye star'. Since Osiris is represented by an eye and is sometimes considered 'the companion of Sirius', this is equivalent to saying that Osiris is 'the eye star', provided only that one grants the premise that the existence of Sirius B really was known to the ancient Egyptians and that 'the companion of Sirius' therefore could ultimately refer to it.

The meanings of the Egyptian hieroglyphs and names for Isis and Osiris were unknown to the earliest dynastic Egyptians themselves, and the names and signs appear to have a pre-dynastic origin -- which means around or before 3200 B.C., in other words 5,000 years ago at least. There has been no living traditional explanation for the meanings of the names and signs for Isis and Osiris since at least 2800 B.C. at the very latest.

'The Dog Star' is a common designation of Sirius throughout known history. The ancient god Anubis was a 'dog god', that is, he had a man's body and a dog's head.

In discussing Egyptian beliefs, Plutarch says that Anubis was really the son of Nephthys, sister to Isis, although he was said to be the son of Isis. Nephthys was 'invisible', Isis was 'visible'. (In other words, the visible mother was the stand-in for the invisible mother, who was the true mother, for the simple reason that the invisible mother could not be perceived.)

Plutarch said that Anubis was a

'horizontal circle, which divides the invisible part ... which they call Nephthys, from the visible, to which they give the name Isis; and as this circle equally touches upon the confines of both light and darkness, it may be looked upon as common to them both.'

This is as clear an ancient description as one could expect of a circular

orbit (called 'Anubis') of a dark and invisible star

(called 'Nephthys')

around its 'sister', a light and visible star (called 'Isis) -- and we know

Isis to have been equated with Sirius.

What is missing here are the

following specific points which must be at this stage still our assumptions:

(a) The circle is actually an orbit(b) The divine characters are actually stars, specifically in this context

Actually, Anubis and

Osiris were sometimes identified with one another. Osiris, the companion of Isis who is sometimes 'the companion of Sirius' is

also sometimes identified with the orbit of the companion of Sirius, and

this is reasonable and to be expected.

Isis-as-Sirius was customarily portrayed by the ancient Egyptians in their paintings as traveling with two companions in the same celestial boat. And as we know, Sirius does, according to some astronomers, have two companions, Sirius B and Sirius C.

To the Arabs, a companion-star to Sirius (in the same constellation of the Great Dog) was named 'Weight' and was supposed to be extremely heavy -- almost too heavy to rise over the horizon. 'Ideler calls this an astonishing star-name', we are told, not surprisingly.

The true companion-star of Sirius, Sirius B, is made of super-dense matter which is heavier than any normal matter in the universe and the weight of this tiny star is the same as that of a gigantic normal star.

The Dogon also, as we know, say that Sirius B is 'heavy' and they speak of its 'weight'.

The Arabs also applied the name 'Weight' to the star Canopus in the constellation Argo. The Argo was a ship in mythology which carried Danaos and his fifty daughters to Rhodes. The Argo had fifty oarsmen under Jason, called Argonauts. There were fifty oars to the Argo, each with its oarsman-Argonaut. The divine oarsman was an ancient Mediterranean motif with sacred meanings.

The orbit of Sirius B around Sirius A takes fifty years, which may be related to the use of the number fifty to describe aspects of the Argo.

There are many divine names and other points in common between ancient Egypt and ancient Sumer (Babylonia). The Sumerians seem to have called Egypt by the name of 'Magan' and to have been in contact with it.

The chief god of Sumer, named Anu, was pictured as a jackal, which is a variation of the dog motif and was used also in Egypt for Anubis, the dog and the jackal apparently being interchangeable as symbols. The Egyptian form of the name Anubis is 'Anpu' and is similar to the Sumerian 'Anu', and both are jackal-gods.

The famous Egyptologist Wallis Budge was convinced that Sumer and Egypt both derived their own cultures from a common source which was 'exceedingly ancient'.

Anu is also called An (a variation) by the Sumerians. In Egypt Osiris is called An also.

Remembering that Plutarch said that Anubis (Anpu in Egyptian) was a circle, it is interesting to note that in Sanskrit the word Anda means 'ellipse'. This may be a coincidence.

Wallis Budge says that Anubis represents time. The combined meanings of 'time' and 'circle' for Anubis hint strongly at 'circular motion'.

The worship of Anubis was a secret mystery religion restricted to initiates (and we thus do not know its content). Plutarch who writes of Anubis, was an initiate of several mystery religions, and there is reason to believe his information was from well-informed sources. (Plutarch himself was a Greek living under the Roman Empire.) A variant translation of Plutarch's description of Anubis is that Anubis was 'a combined relation' between Isis and Nephthys. This has overtones which help in thinking of 'the circle' as an orbit - a 'combined relation' between the star orbiting and the star orbited.

The Egyptians used the name Horus to describe 'the power which is assigned to direct the revolution of the sun', according to Plutarch. Thus the Egyptians conceived of and named such specific dynamics -- an essential point.

Plutarch says Anubis guarded like a dog and attended on Isis. This fact, plus Anubis being 'time' and 'a circle', suggests even more an orbital concept -- the ideal form of attendance of the prowling guard dog.

Aristotle's friend Eudoxus (who visited Egypt) said that the Egyptians had a tradition that Zeus (chief god of the Greeks whose name is used by Eudoxus to refer to his Egyptian equivalent, which leaves us wondering which Egyptian god is meant - presumably Osiris) could not walk because 'his legs were grown together'. This sounds like an amphibious creature with a tail for swimming instead of legs for walking. It is like the semi-divine creature Oannes, reputed to have brought civilization to the Sumerians, who was amphibious, had a tail instead of legs, and retired to the sea at night.

Plutarch relates Isis to the Greek goddess Athena (daughter of Zeus) and says of them they were both described as 'coming from themselves', and as 'self-impelled motion'. Athena supervised the Argo and placed in its prow the guiding oak timber from Dodona (which is where the Greek ark landed, with the Greek version of the Biblical Noah, Deukalion, and his wife Pyrrha). The Argo thus obtained a distinctive 'self-impelled motion' from Athena, whom Plutarch specifically relates to Isis in this capacity.

The earliest versions of the Argo epic which were written before the time of Homer are unfortunately lost. The surviving version of the epic is good reading but relatively recent (third century B.C.).

The Sumerians had 'fifty heroes', 'fifty great gods', etc., just as the later Greeks with their Argo had 'fifty heroes' and the Argo carried 'fifty daughters of Donaos'.

An Egyptian papyrus says the companion of Isis is 'Lord in the perfect black'. This sounds like the invisible Sirius B. Isis's companion Osiris 'is a dark god'.

The Trismegistic treatise 'The Virgin of the World' from Egypt refers to 'the Black Rite', connected with the 'black' Osiris, as the highest degree of secret initiation possible in the ancient Egyptian religion -- it is the ultimate secret of the mysteries of Isis.

This treatise says Hermes came to earth to teach men civilization and then again 'mounted to the stars', going back to his home and leaving behind the mystery religion of Egypt with its celestial secrets which were some day to be decoded.

There is evidence that 'the Black Rite' did deal with astronomical matters. Hence the Black Rite concerned astronomical matters, the black Osiris, and Isis. The evidence mounts that it may thus have concerned the existence of Sirius B.

A prophecy in the treatise 'The Virgin of the World' maintains that only when men concern themselves with the heavenly bodies and 'chase after them into the height' can men hope to understand the subject-matter of the Black Rite. The understanding of astronomy of today's space age now qualifies us to comprehend the true subject of the Black Rite, if that subject is what we suspect it may be. This was impossible earlier in the history of our planet.

Isis-as-Sirius was customarily portrayed by the ancient Egyptians in their paintings as traveling with two companions in the same celestial boat. And as we know, Sirius does, according to some astronomers, have two companions, Sirius B and Sirius C.

To the Arabs, a companion-star to Sirius (in the same constellation of the Great Dog) was named 'Weight' and was supposed to be extremely heavy -- almost too heavy to rise over the horizon. 'Ideler calls this an astonishing star-name', we are told, not surprisingly.

The true companion-star of Sirius, Sirius B, is made of super-dense matter which is heavier than any normal matter in the universe and the weight of this tiny star is the same as that of a gigantic normal star.

The Dogon also, as we know, say that Sirius B is 'heavy' and they speak of its 'weight'.

The Arabs also applied the name 'Weight' to the star Canopus in the constellation Argo. The Argo was a ship in mythology which carried Danaos and his fifty daughters to Rhodes. The Argo had fifty oarsmen under Jason, called Argonauts. There were fifty oars to the Argo, each with its oarsman-Argonaut. The divine oarsman was an ancient Mediterranean motif with sacred meanings.

The orbit of Sirius B around Sirius A takes fifty years, which may be related to the use of the number fifty to describe aspects of the Argo.

There are many divine names and other points in common between ancient Egypt and ancient Sumer (Babylonia). The Sumerians seem to have called Egypt by the name of 'Magan' and to have been in contact with it.

The chief god of Sumer, named Anu, was pictured as a jackal, which is a variation of the dog motif and was used also in Egypt for Anubis, the dog and the jackal apparently being interchangeable as symbols. The Egyptian form of the name Anubis is 'Anpu' and is similar to the Sumerian 'Anu', and both are jackal-gods.

The famous Egyptologist Wallis Budge was convinced that Sumer and Egypt both derived their own cultures from a common source which was 'exceedingly ancient'.

Anu is also called An (a variation) by the Sumerians. In Egypt Osiris is called An also.

Remembering that Plutarch said that Anubis (Anpu in Egyptian) was a circle, it is interesting to note that in Sanskrit the word Anda means 'ellipse'. This may be a coincidence.

Wallis Budge says that Anubis represents time. The combined meanings of 'time' and 'circle' for Anubis hint strongly at 'circular motion'.

The worship of Anubis was a secret mystery religion restricted to initiates (and we thus do not know its content). Plutarch who writes of Anubis, was an initiate of several mystery religions, and there is reason to believe his information was from well-informed sources. (Plutarch himself was a Greek living under the Roman Empire.) A variant translation of Plutarch's description of Anubis is that Anubis was 'a combined relation' between Isis and Nephthys. This has overtones which help in thinking of 'the circle' as an orbit - a 'combined relation' between the star orbiting and the star orbited.

The Egyptians used the name Horus to describe 'the power which is assigned to direct the revolution of the sun', according to Plutarch. Thus the Egyptians conceived of and named such specific dynamics -- an essential point.

Plutarch says Anubis guarded like a dog and attended on Isis. This fact, plus Anubis being 'time' and 'a circle', suggests even more an orbital concept -- the ideal form of attendance of the prowling guard dog.

Aristotle's friend Eudoxus (who visited Egypt) said that the Egyptians had a tradition that Zeus (chief god of the Greeks whose name is used by Eudoxus to refer to his Egyptian equivalent, which leaves us wondering which Egyptian god is meant - presumably Osiris) could not walk because 'his legs were grown together'. This sounds like an amphibious creature with a tail for swimming instead of legs for walking. It is like the semi-divine creature Oannes, reputed to have brought civilization to the Sumerians, who was amphibious, had a tail instead of legs, and retired to the sea at night.

Plutarch relates Isis to the Greek goddess Athena (daughter of Zeus) and says of them they were both described as 'coming from themselves', and as 'self-impelled motion'. Athena supervised the Argo and placed in its prow the guiding oak timber from Dodona (which is where the Greek ark landed, with the Greek version of the Biblical Noah, Deukalion, and his wife Pyrrha). The Argo thus obtained a distinctive 'self-impelled motion' from Athena, whom Plutarch specifically relates to Isis in this capacity.

The earliest versions of the Argo epic which were written before the time of Homer are unfortunately lost. The surviving version of the epic is good reading but relatively recent (third century B.C.).

The Sumerians had 'fifty heroes', 'fifty great gods', etc., just as the later Greeks with their Argo had 'fifty heroes' and the Argo carried 'fifty daughters of Donaos'.

An Egyptian papyrus says the companion of Isis is 'Lord in the perfect black'. This sounds like the invisible Sirius B. Isis's companion Osiris 'is a dark god'.

The Trismegistic treatise 'The Virgin of the World' from Egypt refers to 'the Black Rite', connected with the 'black' Osiris, as the highest degree of secret initiation possible in the ancient Egyptian religion -- it is the ultimate secret of the mysteries of Isis.

This treatise says Hermes came to earth to teach men civilization and then again 'mounted to the stars', going back to his home and leaving behind the mystery religion of Egypt with its celestial secrets which were some day to be decoded.

There is evidence that 'the Black Rite' did deal with astronomical matters. Hence the Black Rite concerned astronomical matters, the black Osiris, and Isis. The evidence mounts that it may thus have concerned the existence of Sirius B.

A prophecy in the treatise 'The Virgin of the World' maintains that only when men concern themselves with the heavenly bodies and 'chase after them into the height' can men hope to understand the subject-matter of the Black Rite. The understanding of astronomy of today's space age now qualifies us to comprehend the true subject of the Black Rite, if that subject is what we suspect it may be. This was impossible earlier in the history of our planet.

It must be remembered that without our present knowledge of white dwarf

stars which are invisible except with modern telescopes, our knowledge of

super-dense matter from atomic physics with all its complicated technology,

etc., none of our discussion of the Sirius system would be possible; it

would not be possible to propose such an explanation of the Black Rite at

all -- we could not propound the Sirius question.

Much material about the Sumerians and Babylonians has only been circulated since the late 1950s and during the 1960s, and our knowledge of pulsars is even more recent than that. It is doubtful that this book could have been written much earlier than the present. The author began work in earnest in 1967 and finished the book in 1974.

Much material about the Sumerians and Babylonians has only been circulated since the late 1950s and during the 1960s, and our knowledge of pulsars is even more recent than that. It is doubtful that this book could have been written much earlier than the present. The author began work in earnest in 1967 and finished the book in 1974.

A bad witch's blog: News: Persecution, Witchcraft, Archaeology, Trees

A bad witch's blog: News: Persecution, Witchcraft, Archaeology, Trees: "Thousands of women tortured and executed in Indian witch hunts" - story on The Sydney Morning Herald website . "Is there a...

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

Magickal News

Samantha Colley as Abigail Williams (top center), with other cast members in a scene from The Crucible

10 must-see cave paintings

http://www.heritagedaily.com/2014/07/10-must-see-cave-paintings/104127?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+HeritageDaily+%28Heritage+Daily+-+Archaeology+%26+Palaeontology+News%29

Pomegranate

http://www.equinoxpub.com/journals/index.php/POM

The Horse Boy and Shamans

http://blog.chasclifton.com/?p=6561

Historical tour in Danvers planned Friday

http://danvers.wickedlocal.com/article/20140710/NEWS/140719660

The Witches of West End

Throwback Thursday: The First Salem Witch Is Executed

10 must-see cave paintings

http://www.heritagedaily.com/2014/07/10-must-see-cave-paintings/104127?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+HeritageDaily+%28Heritage+Daily+-+Archaeology+%26+Palaeontology+News%29

Pomegranate

http://www.equinoxpub.com/journals/index.php/POM

The Horse Boy and Shamans

http://blog.chasclifton.com/?p=6561

Historical tour in Danvers planned Friday

http://danvers.wickedlocal.com/article/20140710/NEWS/140719660

The Witches of West End

Uncover the truth behind Scotland's infamous witch trials

Sunday, July 13, 2014

Saturday, July 12, 2014

John Dee July 13th

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, occultist, imperialist[5] and adviser to Queen Elizabeth I. He devoted much of his life to the study of alchemy, divination and Hermetic philosophy.

Dee straddled the worlds of science and magic just as they were becoming distinguishable. One of the most learned men of his age, he had been invited to lecture on advanced algebra at the University of Paris while still in his early twenties. Dee was an ardent promoter of mathematics and a respected astronomer, as well as a leading expert in navigation, having trained many of those who would conduct England's voyages of discovery.

Simultaneously with these efforts, Dee immersed himself in the worlds of magic, astrology and Hermetic philosophy. He devoted much time and effort in the last thirty years or so of his life to attempting to commune with angels in order to learn the universal language of creation and bring about the pre-apocalyptic unity of mankind. A student of the Renaissance Neo-Platonism of Marsilio Ficino, Dee did not draw distinctions between his mathematical research and his investigations into Hermetic magic, angel summoning and divination. Instead he considered all of his activities to constitute different facets of the same quest: the search for a transcendent understanding of the divine forms which underlie the visible world, which Dee called "pure verities".

In his lifetime Dee amassed one of the largest libraries in England. His high status as a scholar also allowed him to play a role in Elizabethan politics. He served as an occasional adviser and tutor to Elizabeth I and nurtured relationships with her ministers Francis Walsingham and William Cecil. Dee also tutored and enjoyed patronage relationships with Sir Philip Sidney, his uncle Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, and Edward Dyer. He also enjoyed patronage from Sir Christopher Hatton.

| Born | 13 July 1527[2] Tower Ward, London[2] |

|---|---|

| Died | December 1608 or March 1609 Mortlake, Surrey, England |

| Residence | England |

| Nationality | English |

| Fields | Mathematics, alchemy, astrology, Hermeticism, navigation, |

| Institutions | Christ's College, Manchester, St John's College, Cambridge |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge Louvain University |

| Academic advisors | Gemma Frisius, Gerardus Mercator[3] |

| Notable students | Thomas Digges[4] |

| Known for | Advisor to Queen Elizabeth I |

BiographyEarly lifeDee was born in Tower Ward, London, in a Welsh[6] family from Radnorshire. He was the only child of his parents: Rowland, who was a mercer and minor courtier, and Jane, who was the daughter of William Wild.[5]Dee attended the Chelmsford Chantry School from 1535 (now King Edward VI Grammar School (Chelmsford)), then – from November 1542 to 1546 – St. John's College, Cambridge.[7] His great abilities were recognised, and he was made a founding fellow of Trinity College, where the clever stage effects he produced for a production of Aristophanes' Peace procured him the reputation of being a magician that clung to him through life. In the late 1540s and early 1550s, he travelled in Europe, studying at Louvain (1548) and Brussels and lecturing in Paris on Euclid. He studied with Gemma Frisius and became a close friend of the cartographer Gerardus Mercator, returning to England with an important collection of mathematical and astronomical instruments. In 1552, he met Gerolamo Cardano in London: during their acquaintance they investigated a perpetual motion machine as well as a gem purported to have magical properties.[8] Rector at Upton-upon-Severn from 1553, Dee was offered a readership in mathematics at Oxford in 1554, which he declined; he was occupied with writing and perhaps hoped for a better position at court.[9] In 1555, Dee became a member of the Worshipful Company of Mercers, as his father had, through the company's system of patrimony.[10] That same year, 1555, he was arrested and charged with "calculating" for having cast horoscopes of Queen Mary and Princess Elizabeth; the charges were expanded to treason against Mary.[9][11] Dee appeared in the Star Chamber and exonerated himself, but was turned over to the Catholic Bishop Bonner for religious examination. His strong and lifelong penchant for secrecy perhaps worsening matters, this entire episode was only the most dramatic in a series of attacks and slanders that would dog Dee throughout his life. Clearing his name yet again, he soon became a close associate of Bonner.[9] Dee presented Queen Mary with a visionary plan for the preservation of old books, manuscripts and records and the founding of a national library, in 1556, but his proposal was not taken up.[9] Instead, he expanded his personal library at his house in Mortlake, tirelessly acquiring books and manuscripts in England and on the European Continent. Dee's library, a centre of learning outside the universities, became the greatest in England and attracted many scholars.[12]

Dee's glyph, whose meaning he explained in Monas Hieroglyphica.

In 1564, Dee wrote the Hermetic work Monas Hieroglyphica ("The Hieroglyphic Monad"), an exhaustive Cabalistic interpretation of a glyph of his own design, meant to express the mystical unity of all creation. He travelled to Hungary to present a copy personally to Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor. This work was highly valued by many of Dee's contemporaries, but the loss of the secret oral tradition of Dee's milieu makes the work difficult to interpret today.[17] He published a "Mathematical Preface" to Henry Billingsley's English translation of Euclid's Elements in 1570, arguing the central importance of mathematics and outlining mathematics' influence on the other arts and sciences.[18] Intended for an audience outside the universities, it proved to be Dee's most widely influential and frequently reprinted work.[19] Later life

The "Seal of God", British Museum (see below)

Dee's first attempts were not satisfactory, but, in 1582, he met Edward Kelley (then going under the name of Edward Talbot), who impressed him greatly with his abilities.[21] Dee took Kelley into his service and began to devote all his energies to his supernatural pursuits.[21] These "spiritual conferences" or "actions" were conducted with an air of intense Christian piety, always after periods of purification, prayer and fasting.[21] Dee was convinced of the benefits they could bring to mankind. (The character of Kelley is harder to assess: some have concluded that he acted with complete cynicism, but delusion or self-deception are not out of the question.[22] Kelley's "output" is remarkable for its sheer mass, its intricacy and its vividness). Dee maintained that the angels laboriously dictated several books to him this way, some in a special angelic or Enochian language.[23][24] In 1583, Dee met the visiting Polish nobleman Albert Łaski, who invited Dee to accompany him on his return to Poland.[11] With some prompting by the angels, Dee was persuaded to go. Dee, Kelley and their families left for the Continent in September 1583, but Łaski proved to be bankrupt and out of favour in his own country.[25] Dee and Kelley began a nomadic life in Central Europe, but they continued their spiritual conferences, which Dee recorded meticulously.[23][24] He had audiences with Emperor Rudolf II in Prague Castle and King Stefan Batory of Poland and attempted to convince them of the importance of his angelic communications. His meeting with the Polish King, Stefan Batory, took place at the royal castle at Niepołomice (near Kraków, then the capital of Poland) and was later widely analysed by Polish historians (Ryszard Zieliński, Roman Żelewski, Roman Bugaj) and writers (Waldemar Łysiak). While generally they accepted him as being a man of wide and deep knowledge, they also pointed out his connections with the English monarch, Elizabeth. From this they concluded that the meeting could have hidden political goals. Nevertheless, the Polish King who, being a devout Catholic, was very cautious of any supernatural media, started the meeting with a statement that all prophetic revelations were finalised with the mission of Jesus Christ. He also stressed that he would take part in the event provided that there would be nothing against the teaching of the Holy Catholic Church. During a spiritual conference in Bohemia, in 1587, Kelley told Dee that the angel Uriel had ordered that the two men should share their wives. Kelley, who by that time was becoming a prominent alchemist and was much more sought-after than Dee, may have wished to use this as a way to end the spiritual conferences.[25] The order caused Dee great anguish, but he did not doubt its genuineness and apparently allowed it to go forward, but broke off the conferences immediately afterwards and did not see Kelley again. Dee returned to England in 1589.[25][26] Final years

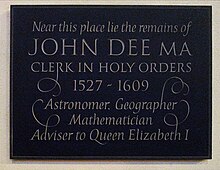

John Dee memorial plaque installed in 2013 inside the church of St Mary the Virgin Mortlake

However, he could not exert much control over the Fellows, who despised or cheated him.[9] Early in his tenure, he was consulted on the demonic possession of seven children, but took little interest in the matter, although he did allow those involved to consult his still extensive library.[9] He left Manchester in 1605 to return to London;[29] however, he remained Warden until his death.[30] By that time, Elizabeth was dead, and James I provided no support. Dee spent his final years in poverty at Mortlake, forced to sell off various of his possessions to support himself and his daughter, Katherine, who cared for him until the end.[29] He died in Mortlake late in 1608 or early 1609 aged 82 (there are no extant records of the exact date as both the parish registers and Dee's gravestone are missing).[9][31] In 2013 a memorial plaque to Dee was placed on the south wall of the present church.[32] Personal lifeDee was married twice and had eight children. He first married Katherine Constable in 1565; their marriage ended in 1575 and resulted in no children. From 1577 to 1601 Dee kept a sporadic diary.[10] In 1578 he married the 23-year-old Jane Fromond (Dee was fifty-one at the time). She was to be the wife that Kelley claimed Uriel had demanded that he and Dee share, and although Dee complied for a while this eventually caused the two men to part company.[10] Jane died during the plague in Manchester and was buried in March 1604,[33] along with a number of his children: Theodore is known to have died in Manchester, but although no records exist for his daughters Madinia, Frances and Margaret after this time, Dee had by this time ceased keeping his diary.[9] His eldest son was Arthur Dee, about whom Dee wrote a letter to his headmaster at Westminster School which echoes the worries of boarding school parents in every century; Arthur was also an alchemist and hermetic author.[9] The antiquary John Aubrey[34] gives the following description of John Dee: "He was tall and slender. He wore a gown like an artist's gown, with hanging sleeves, and a slit.... A very fair, clear sanguine complexion... a long beard as white as milk. A very handsome man."[31]AchievementsThoughtDee was an intensely pious Christian, but his Christianity was deeply influenced by the Hermetic and Platonic-Pythagorean doctrines that were pervasive in the Renaissance.[35] He believed that numbers were the basis of all things and the key to knowledge, that God's creation was an act of numbering.[13] From Hermeticism, he drew the belief that man had the potential for divine power, and he believed this divine power could be exercised through mathematics. His cabalistic angel magic (which was heavily numerological) and his work on practical mathematics (navigation, for example) were simply the exalted and mundane ends of the same spectrum, not the antithetical activities many would see them as today.[19] His ultimate goal was to help bring forth a unified world religion through the healing of the breach of the Catholic and Protestant churches and the recapture of the pure theology of the ancients.[13]Advocacy of English expansionFrom 1570 Dee advocated a policy of political and economic strengthening of England and imperial expansion into the New World.[5] In his manuscript, Brytannicae reipublicae synopsis (1570), he outlined the current state of the Elizabethan Realm[36] and was concerned with trade, ethics and national strength.[5]His 1576 General and rare memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation, was the first volume in an unfinished series planned to advocate the rise of imperial expansion.[37] In the highly symbolic frontispiece, Dee included a figure of Britannia kneeling by the shore beseeching Elizabeth I, to protect her empire by strengthening her navy.[38] Dee used Geoffrey's inclusion of Ireland in Arthur's imperial conquests to argue that Arthur had established a 'British empire' abroad.[39] He further argued that England exploit new lands through colonisation and that this vision could become reality through maritime supremacy.[40][41] Dee has been credited with the coining of the term British Empire,[42] however, Humphrey Llwyd has also been credited with the first use of the term in his Commentarioli Britannicae Descriptionis Fragmentum, published eight years earlier in 1568.[43] Dee posited a formal claim to North America on the back of a map drawn in 1577–80;[44] he noted Circa 1494 Mr Robert Thorn his father, and Mr Eliot of Bristow, discovered Newfound Land.[45] In his Title Royal of 1580, he invented the claim that Madog ab Owain Gwynedd had discovered America, with the intention of ensuring that England's claim to the New World was stronger than that of Spain.[46] He further asserted that Brutus of Britain and King Arthur as well as Madog had conquered lands in the Americas and therefore their heir Elizabeth I of England had a priority claim there.[47][48] Reputation and significanceAbout ten years after Dee's death, the antiquarian Robert Cotton purchased land around Dee's house and began digging in search of papers and artifacts. He discovered several manuscripts, mainly records of Dee's angelic communications. Cotton's son gave these manuscripts to the scholar Méric Casaubon, who published them in 1659, together with a long introduction critical of their author, as A True & Faithful Relation of What passed for many Yeers between Dr. John Dee (A Mathematician of Great Fame in Q. Eliz. and King James their Reignes) and some spirits.[23] As the first public revelation of Dee's spiritual conferences, the book was extremely popular and sold quickly. Casaubon, who believed in the reality of spirits, argued in his introduction that Dee was acting as the unwitting tool of evil spirits when he believed he was communicating with angels. This book is largely responsible for the image, prevalent for the following two and a half centuries, of Dee as a dupe and deluded fanatic.[35] Around the same time the True and Faithful Relation was published, members of the Rosicrucian movement claimed Dee as one of their number.[49] There is doubt, however, that an organised Rosicrucian movement existed during Dee's lifetime, and no evidence that he ever belonged to any secret fraternity.[21] Dee's reputation as a magician and the vivid story of his association with Edward Kelley have made him a seemingly irresistible figure to fabulists, writers of horror stories and latter-day magicians. The accretion of false and often fanciful information about Dee often obscures the facts of his life, remarkable as they are in themselves.[50]A re-evaluation of Dee's character and significance came in the 20th century, largely as a result of the work of the historian Frances Yates, who brought a new focus on the role of magic in the Renaissance and the development of modern science. As a result of this re-evaluation, Dee is now viewed as a serious scholar and appreciated as one of the most learned men of his day.[35][51] His personal library at Mortlake was the largest in the country, and was considered one of the finest in Europe, perhaps second only to that of De Thou. As well as being an astrological and scientific advisor to Elizabeth and her court, he was an early advocate of the colonisation of North America and a visionary of a British Empire stretching across the North Atlantic.[15] Dee promoted the sciences of navigation and cartography. He studied closely with Gerardus Mercator, and he owned an important collection of maps, globes and astronomical instruments. He developed new instruments as well as special navigational techniques for use in polar regions. Dee served as an advisor to the English voyages of discovery, and personally selected pilots and trained them in navigation.[9][15] He believed that mathematics (which he understood mystically) was central to the progress of human learning. The centrality of mathematics to Dee's vision makes him to that extent more modern than Francis Bacon, though some scholars believe Bacon purposely downplayed mathematics in the anti-occult atmosphere of the reign of James I.[52] It should be noted, though, that Dee's understanding of the role of mathematics is radically different from our contemporary view.[19][50][53] Dee's promotion of mathematics outside the universities was an enduring practical achievement. His "Mathematical Preface" to Euclid was meant to promote the study and application of mathematics by those without a university education, and was very popular and influential among the "mecanicians": the new and growing class of technical craftsmen and artisans. Dee's preface included demonstrations of mathematical principles that readers could perform themselves.[19] CalendarDee was a friend of Tycho Brahe and was familiar with the work of Nicolaus Copernicus.[9] Many of his astronomical calculations were based on Copernican assumptions, but he never openly espoused the heliocentric theory. Dee applied Copernican theory to the problem of calendar reform. In 1583, he was asked to advise the Queen about the new Gregorian calendar that had been promulgated by Pope Gregory XIII from October 1582. His advice was that England should accept it, albeit with seven specific amendments. The first of these was that the adjustment should not be the 10 days that would restore the calendar to the time of the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, but by 11 days, which would restore it to the birth of Christ. Another proposal of Dee's was to align the civil and liturgical years, and to have them both start on 1 January. Perhaps predictably, England chose to spurn any suggestions that had papist origins, despite any merit they may objectively have, and Dee's advice was rejected.[13]Voynich manuscriptHe has often been associated with the Voynich manuscript.[21][54] Wilfrid Michael Voynich, who bought the manuscript in 1912, suggested that Dee may have owned the manuscript and sold it to Rudolph II. Dee's contacts with Rudolph were far less extensive than had previously been thought, however, and Dee's diaries show no evidence of the sale. Dee was, however, known to have possessed a copy of the Book of Soyga, another enciphered book.[55]Works

Artifacts

Objects used by Dee in his magic, now in the British Museum.

Literary and cultural referencesDee was a popular figure in literary works written by his contemporaries, and he has continued to feature in popular culture ever since, particularly in fiction or fantasy set during his lifetime or that deals with magic or the occult.

Notes

ReferencesPrimary sources

Secondary sources

External links

http://www.john-dee.org/ http://www.dominicselwood.com/dr-john-dee-mathematician-scientist-magus-and-conjuror/ | |||||||||

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![X1 [t] t](http://bits.wikimedia.org/static-1.24wmf11/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_X1.png)